The Story of Cannabis: A Complete Guide to History, Science, and Modern Use

Cannabis is perhaps the most misunderstood organism on Earth. To some, it is a dangerous narcotic; to others, a sacred sacrament, a versatile industrial resource, or a miraculous medicine. In reality, it is all of these and more. As we move further, the veil of prohibition is lifting globally, revealing a complex botanical marvel that has co-evolved with humanity for over ten millennia. This long-read serves as a comprehensive encyclopedia, tracing the journey of Cannabis sativa L. from the ancient steppes of Asia to the high-tech laboratories of the modern medical era.

In the words of eminent American scientist Carl Sagan, there’s a real possibility cannabis may have been the first agricultural crop in the world, contributing to the rise of civilization. The evidence the plant was farmed, traded, and used in textile and pottery is overwhelming.

The Neolithic Dawn: China and the “Five Grains”

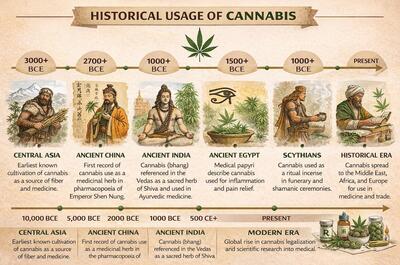

Archaeological evidence from the Oki Islands near Japan and sites in mainland China suggests that humans were using cannabis as early as 8000–10,000 BCE. While many modern readers focus on the “high,” our ancestors focused on the “hold.” The Neolithic Chinese mastered the art of “retting”—soaking stalks to extract long, durable fibers.

By 4000 BCE, hemp was so fundamental to Chinese life that it was categorized as one of the “Five Grains” (Wu Gu), alongside rice and millet. It clothed the peasantry, provided cordage for bowstrings, and became the world’s first paper. The legendary Emperor Shen Nung (c. 2700 BCE), often called the Father of Chinese Medicine, is credited with the first written record of cannabis as a medicinal treatment, prescribing it for over 100 conditions, including gout, malaria, and “absent-mindedness.”

The Sacred Smoke: From the Vedas to the Silk Road

As the plant moved south into India, its spiritual identity took center stage. In the Vedas (sacred Hindu texts), cannabis is hailed as one of the five sacred plants, a “source of happiness” and a “bringer of freedom.” It became the main ingredient in Bhang, a ritualistic drink used to honor Lord Shiva.

Simultaneously, the Scythians—nomadic horse-warriors of the Eurasian steppes—carried the plant westward. The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 440 BCE) famously described Scythian funeral rites where mourners would huddle inside felt “smoke tents,” casting cannabis seeds onto red-hot stones. The resulting vapor, Herodotus noted, made them “howl with joy.” This represents the earliest documented form of communal vaporization in history.

Cannabis in the Afterlife? Pollen Traces Found on Egyptian Mummies

Traces of the plant have been found in ancient Egypt and the ancient Middle East as well. The mummy of Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II reportedly carried traces of cannabis pollen, while deciphered hieroglyphs suggest the plant was valued for its anti-inflammatory properties. It was used to treat glaucoma and, in some accounts, even administered rectally to cleanse the bowels (an early form of enema). Ancient Persian texts also list cannabis among the most important medicinal herbs in the region. From inflammation to a range of other maladies, early societies were clearly aware of—and practiced—multiple medical applications of the plant.

While cannabis was often consumed externally as a balm or smoked, 19th-century records show that the plant’s flowering tops were sometimes used internally to address conditions such as angina pectoris and gonorrhea, according to Britannica. During that same century, cannabis became a common analgesic in parts of Western medicine. Physicians prescribed it for general pain, migraines, stomach discomfort, and muscle spasms. It was also used as an anti-seizure remedy and to help patients struggling with insomnia or depression.

The Queen’s Remedy? How Cannabis Reached the Royal Court

Cannabis’ formal introduction into Western medical practice is often attributed to the 19th-century Irish physician Dr. William Brooke O’Shaughnessy. His work in India helped document the plant’s therapeutic potential and bring cannabis preparations into British and European pharmacopeias.

Perhaps one of the most entertaining chapters in the history of medical cannabis involves the British royal family. As the story goes, the famously reserved Queen Victoria—often dubbed the “grandmother of Europe”—may have been prescribed cannabis to relieve menstrual cramps. The alleged source was her private physician, Sir J. Russell Reynolds, who wrote in 1890 that “when pure and administered carefully, [cannabis] is one of the most valuable medicines we possess.”

The Queen was hardly a counterculture icon; she would likely have taken cannabis in tincture form—an alcohol-based extract of the plant. Interestingly, tinctures are experiencing renewed interest today. Which attests to the many different ways cannabis can be consumed by the body.

The Modern Chemistry – The Molecular Masterpiece

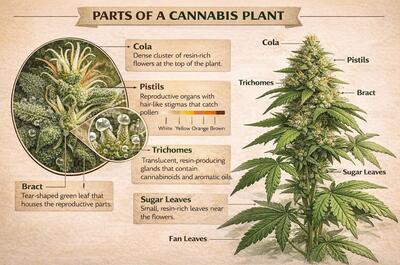

Cannabis users value the plant for its medical and recreational effects, driven by its diverse cannabinoids. These compounds are produced primarily in the resin-rich flowers of female plants—specifically within the dense bud clusters known as colas.

On each bud, pistils house the reproductive organs, with hair-like stigmas that catch pollen during pollination. As the plant matures, these stigmas shift in color from white to yellow, orange, and brown—a visual cue growers use to gauge ripeness.

Encasing the reproductive parts are tear-shaped bracts, which contain some of the highest concentrations of resin glands on the plant. At the base sits the calyx, adding another protective layer. Covering the flowers and nearby leaves are translucent, bulbous trichomes—microscopic glands responsible for producing most cannabinoids as well as the aromatic oils that define a strain’s scent and flavor.

Yet understanding where cannabinoids are produced is only half the story. The real intrigue begins once those resin-packed trichomes are harvested, heated, and introduced into the human body. The chemistry of the plant meets the chemistry of us. What makes these compounds so uniquely effective is not just their presence in the flower, but the remarkable biological system within our own bodies that recognizes and responds to them.

The Endocannabinoid System (ECS): The Body’s Master Regulator

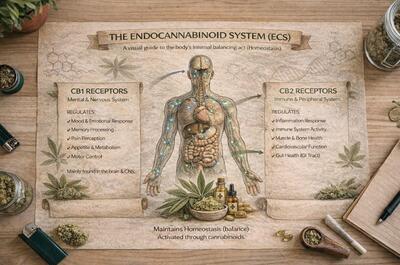

In the early 1990s, researchers discovered a vast signaling network within the human body called the Endocannabinoid System (ECS). This system acts as a “dimmer switch” for our central nervous system, maintaining homeostasis (balance) in sleep, mood, pain perception, and immune response.

We possess two primary types of receptors:

- CB1 Receptors: Concentrated in the brain and central nervous system. These are the primary “locks” that THC unlocks to produce a psychoactive effect.

- CB2 Receptors: Found mostly in the immune system and peripheral organs. These are the primary targets for anti-inflammatory and non-intoxicating treatments.

Beyond THC and CBD: Cannabis Carries Hundreds of Cannabinoids

For most of the past decades, scientists and consumers focused almost exclusively on the “Big Two.” Today, however, research has identified more than 100 cannabinoids, each with distinct characteristics and potential applications. Beyond THC and CBD, here are several that are drawing serious attention:

- THCP (Tetrahydrocannabiphorol): A naturally occurring cannabinoid shown to bind to CB1 receptors with significantly greater affinity than delta-9 THC. Its potency may help explain why some cultivars with modest THC percentages can feel unexpectedly intense.

- CBG (Cannabigerol): Often called the “Mother Cannabinoid,” CBG is the precursor from which THC, CBD, and CBC are synthesized. Early research is exploring its potential neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties.

- CBN (Cannabinol): Formed as THC oxidizes over time, CBN is commonly associated with deeply relaxing effects. It has gained popularity in sleep-focused formulations and nighttime products.

- CBC (Cannabichromene): A non-intoxicating cannabinoid believed to interact with different receptor pathways than THC. Researchers are studying CBC for its potential role in mood regulation and inflammation response.

- THCV (Tetrahydrocannabivarin): Structurally similar to THC but with a notably different effect profile. At lower doses, THCV is often described as clear-headed and energizing. It is also being studied for its possible influence on appetite and metabolic processes.

- CBDV (Cannabidivarin): A close relative of CBD, CBDV is under investigation for its potential role in neurological conditions, particularly seizure-related disorders.

- CBGA (Cannabigerolic Acid): The acidic precursor to CBG, THC, and CBD. While it converts into other cannabinoids through heat and time, researchers are examining its independent biological activity.

- Delta-8-THC: A naturally occurring minor cannabinoid (often produced from hemp-derived CBD in commercial settings) known for producing milder psychoactive effects compared to delta-9 THC.

- HHC (Hexahydrocannabinol): A hydrogenated form of THC that occurs in trace amounts naturally but is typically produced semi-synthetically. It is reported to offer THC-like effects with slightly different potency and duration.

As cannabinoid science evolves, the conversation is shifting from a THC-versus-CBD binary to a broader understanding of how these compounds work together—reinforcing the idea that the plant’s complexity, not just its headline molecule, shapes the overall experience.

The Entourage Effect and Terpenes

Modern connoisseurs no longer simply ask for “Sativa” or “Indica.” They also look for the Terpene Profile. Terpenes are the aromatic oils—like Myrcene (clove-like), Limonene (citrus), and Pinene (pine)—that dictate the “shape” of the high. These compounds evolved to protect against pests, fungi, and grazing animals. The Entourage Effect describes how these oils work synergistically with cannabinoids to produce a more balanced medical or recreational effect than isolated chemicals can achieve.

The Century of Shadow: Prohibition and Resilience

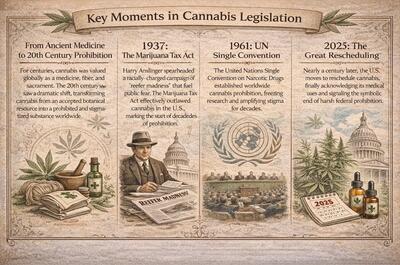

For most of recorded history, cannabis moved through civilizations as medicine, fiber, ritual sacrament, and trade commodity. But the 20th century marked a dramatic rupture. What had long been a botanical constant became a political target—ushering in decades of prohibition that reshaped global policy and public perception.

The 1937 Marijuana Tax Act

Cannabis criminalization in the 20th century was driven less by emerging medical evidence and more by political momentum, economic interests, and cultural anxiety. In the United States, Harry Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, spearheaded a campaign that strategically reframed cannabis as marijuana—a term emphasized to associate the plant with Mexican immigrants and other marginalized communities.

Through sensationalized media narratives and racially charged rhetoric, cannabis was linked to crime, moral decay, and social instability. The result was the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, which imposed prohibitive regulations and effectively dismantled legal hemp production and medical cannabis use in the U.S.

The American stance did not remain domestic policy for long. In 1961, the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs codified cannabis prohibition on a global scale, pressuring signatory nations to criminalize the plant. What followed was a near-century of restricted research, underground markets, and cultural stigma— even as illicit use persisted worldwide.

Rescheduling Cannabis: A Turning Point?

Since last year, 2025, the narrative has finally started to shift decisively. The U.S. government’s move to reclassify cannabis to Schedule III marks the most significant federal policy change in generations. For the first time in nearly a century, the government formally acknowledges that cannabis has “currently accepted medical use.”

While this shift would not equal full legalization, it signals the symbolic end of harsh federal prohibition. Rescheduling is expected to ease tax burdens for licensed operators, re-engage universities in cannabis research, and soften institutional stigma. For many advocates, it represents the closing chapter of cannabis’ Dark Ages.

The 2018 Farm Bill Legacy

In the meantime, the 2018 Farm Bill produced an unintended revolution. By legalizing hemp—defined as cannabis containing less than 0.3% Delta-9 THC—lawmakers opened the door to a vast new marketplace.

Entrepreneurs quickly leveraged hemp-derived CBD to synthesize and market psychoactive cannabinoids such as Delta-8 THC, Delta-10, and other novel compounds. This created a multi-billion-dollar gray-zone industry operating in states where traditional cannabis remained illegal. But it also left regulators grappling with the consequences: inconsistent testing standards, patchwork state bans, and ongoing debates over consumer safety and federal oversight.

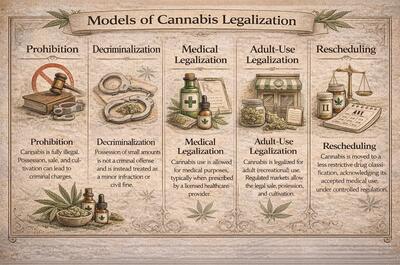

The Global Landscape: A World in Transition

While North America often dominates the headlines, the global approach to cannabis is no longer monolithic. From social clubs in Europe to constitutional victories in the Global South, the legal framework is shifting from criminalization to regulated management.

Europe: The Continent of Experiments

Europe has avoided the “Big Retail” model of the U.S., opting instead for public health-centric pilots and non-profit models.

- Germany (The CanG Model): Legalized in 2024, Germany’s framework is the most influential in the EU. It permits personal possession (up to 25g) and home cultivation (3 plants). The heart of the model is the Cannabis Social Club, a non-profit cooperative where members can collectively grow and distribute cannabis.

- Malta: The first EU nation to fully legalize. Malta allows adults to carry up to 7g and grow four plants at home, with distribution handled through regulated non-profit associations.

- Luxembourg: Permits home cultivation and private consumption, focusing on a “personal freedom” model rather than a commercial one.

- Czechia: Currently developing a regulated market. Prague is moving toward a system that may include a commercial pilot, heavily inspired by Germany’s progress but potentially more retail-friendly.

- Switzerland & The Netherlands: Both nations are running city-wide “closed-loop” experiments. Switzerland’s Trial Cities (like Zurich and Basel) and the Dutch Wietexperiment allow legal production and sales in specific municipalities to study the impact on crime and health.

The Americas: Beyond the United States

- Canada (The G7 Pioneer): Since 2018, Canada has operated a nationwide commercial market. It remains the global gold standard for federal regulation, balancing a multi-billion dollar industry with strict rules on plain packaging and youth prevention.

- Mexico: Following a landmark Supreme Court ruling, Mexico is in a unique state of “decriminalized limbo.” While the court declared prohibition unconstitutional, the legislature is still refining the commercial framework. Currently, personal possession and private cultivation are protected under “the right to the free development of personality.”

- Uruguay: The first country in the world to legalize (2013). Its state-controlled model allows for three paths: home grow, social clubs, or purchasing state-regulated cannabis at pharmacies.

Africa & Southeast Asia: Changing Tides

- South Africa: In 2018, the Constitutional Court decriminalized the private use and cultivation of cannabis by adults. In 2024, the Cannabis for Private Purposes Act was signed into law, formalizing the right of adults to possess and grow the plant, though commercial retail remains prohibited.

- Thailand: The first Southeast Asian nation to decriminalize (2022). After an initial “Green Rush,” the government is currently tightening regulations to pivot the industry back toward strictly medical and health-focused use, ending the era of unregulated “dispensary cafes” while keeping the plant legal for therapeutic purposes.

Medical Evidence and Modern Applications

Disclaimer: This section is for informational purposes only. Always consult a qualified medical professional before starting any treatment with cannabis medicines.

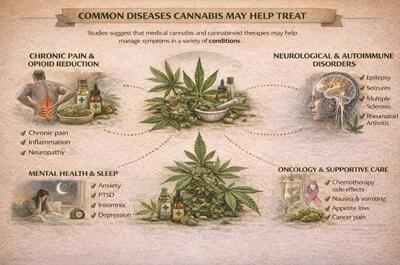

Chronic Pain and Opioid Reduction

One of the most significant breakthroughs in recent years is the growing use of cannabis as what some researchers call an “exit drug.” In regions with regulated access, studies have observed measurable declines in opioid prescriptions and, in some cases, opioid-related harms, as patients substitute cannabis for chronic pain management.

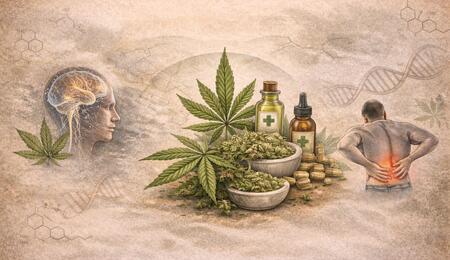

Cannabinoids such as THC and CBD interact with the body’s endocannabinoid system, which plays a key role in pain signaling and inflammation. Patients with conditions such as neuropathic pain, arthritis, fibromyalgia, lower back pain, and cancer-related pain commonly report symptom relief, often with a different side-effect profile than traditional opioids.

Neurological and Autoimmune Disorders

- Epilepsy: CBD-based medicines (such as Epidiolex) remain a landmark development for treatment-resistant seizure disorders, including Dravet syndrome and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): THC:CBD oromucosal sprays are widely prescribed in several countries to treat spasticity, muscle stiffness, and tremors associated with MS.

- Parkinson’s Disease: Emerging research is exploring cannabis for tremor reduction, sleep disturbances, and quality-of-life improvements, though results remain mixed and patient-specific.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Preliminary studies suggest that the anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids such as CBD and CBG may help reduce gut inflammation and improve symptom control in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Autoimmune Conditions: Because cannabinoids can modulate immune signaling and inflammation, patients with autoimmune disorders often report relief from joint pain, stiffness, and sleep disruption. Clinical evidence is still developing, but interest is strong.

Mental Health and Sleep

- Anxiety Disorders: Low-to-moderate doses of CBD are widely used for generalized anxiety and social anxiety symptoms. THC-rich products, however, may worsen anxiety in some individuals, underscoring the importance of personalized dosing.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Cannabis is frequently used to address nightmares, hyperarousal, and sleep disturbances. Some observational studies suggest symptom reduction, though long-term data are still being evaluated.

- Insomnia: THC, CBN-dominant formulations, and balanced THC:CBD products are increasingly marketed for sleep support, particularly in patients whose insomnia is linked to chronic pain or anxiety.

Oncology and Supportive Cancer Care

While cannabis is not a cure for cancer, it is widely used in supportive care. Patients undergoing chemotherapy often rely on cannabinoids to reduce nausea and vomiting, stimulate appetite, ease neuropathic pain, and improve sleep. Synthetic THC analogues have long been approved in certain jurisdictions for chemotherapy-induced nausea.

Across these categories, one theme remains consistent: cannabis is rarely a one-size-fits-all solution. Its therapeutic potential appears strongest when carefully dosed, medically supervised, and integrated into a broader treatment plan.

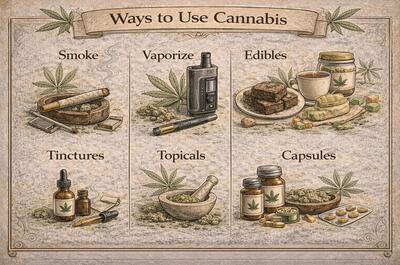

Recreational Consumption & Safety: The Responsible Connoisseur

As cannabis culture matures, so does the conversation around how it’s consumed. Today’s responsible connoisseur isn’t just chasing flavor or potency—they’re thinking about bioavailability, long-term health, and dose control.

Vaporization vs. Combustion

Health-conscious users continue moving away from traditional smoking. Combustion—the act of burning plant material—produces tar, carbon monoxide, and other potentially harmful byproducts.

Dry-herb vaporization, by contrast, heats cannabis to controlled temperatures that release cannabinoids and terpenes without igniting the plant matter. This allows users to:

- Target specific temperature ranges for desired effects (e.g., lighter terpene expression at lower temps, fuller cannabinoid release at higher temps)

- Reduce exposure to combustion-related toxins

- Experience cleaner flavor profiles

While inhalation of any substance carries risk, vaporization is widely considered a harm-reduction approach compared to smoking.

The Edible Learning Curve

Edibles remain one of the most misunderstood consumption methods. When cannabis is ingested, the liver metabolizes Delta-9 THC into 11-Hydroxy-THC, a compound that crosses the blood–brain barrier more efficiently and often produces stronger, longer-lasting effects.

- Onset Time: Can range from 30 minutes to two hours, depending on metabolism, body composition, and whether food was consumed beforehand. Effects may last six to eight hours—sometimes longer.

- The Golden Rule: It remains timeless, “Start low, go slow.”

- Safe Dosing: For many adults, it is beginning with 2.5–5 mg of THC and waiting a full two hours before considering more.

Tinctures and Sublinguals

Alcohol- or oil-based cannabis extracts taken under the tongue offer a middle ground between inhalation and edibles. Absorbed through the mucous membranes, sublingual products often produce effects within 15–45 minutes and allow for more precise dosing. Tinctures and sublinguals are widely used among medical patients seeking discretion and predictable onset.

Topicals and Transdermals

Cannabis-infused creams, balms, and patches are used for localized relief of muscle soreness, joint pain, and inflammation.

- Topicals generally do not produce intoxicating effects, as cannabinoids do not significantly enter the bloodstream.

- Transdermal patches, however, are designed to deliver cannabinoids systemically over extended periods.

Concentrates and High-Potency Products

Dabs, live resins, rosin, and vape cartridges can contain very high concentrations of THC. While they offer intense terpene expression and rapid onset, they also increase the risk of overconsumption, especially for inexperienced users.

Responsible use includes:

- Understanding potency percentages

- Using measured devices

- Avoiding mixing with alcohol or other intoxicants

General Safety Principles

- Avoid driving or operating machinery while impaired.

- Be mindful of interactions with prescription medications.

- Store products securely away from children and pets.

- Individuals with a history of psychosis or certain cardiovascular conditions should consult a physician before use.

Useful Glossary for the Modern Cannabis User

- Decarboxylation: The process of heating cannabis to “activate” cannabinoids. Raw THCA and CBDA convert into THC and CBD through heat, making them psychoactive or more bioavailable.

- Trichomes: The tiny, crystal-like resin glands that coat cannabis flowers and small leaves. They produce and store cannabinoids, terpenes, and other aromatic compounds.

- Full-Spectrum: Products that contain the plant’s full range of naturally occurring cannabinoids, terpenes, and minor compounds — designed to preserve the entourage effect.

- Broad-Spectrum: Similar to full-spectrum but typically formulated without THC, while retaining other cannabinoids and terpenes.

- Isolate: A purified form of a single cannabinoid (such as CBD isolate) with all other plant compounds removed.

- Flower vs. Concentrate: “Flower” refers to the dried, cured buds of the cannabis plant. “Concentrates” (wax, shatter, rosin, live resin) are extracted forms containing high levels of cannabinoids and terpenes.

- Rosin: A solventless concentrate made using only heat and pressure to extract resin from flower or hash.

- Live Resin: A concentrate produced from freshly harvested, flash-frozen cannabis to preserve volatile terpenes and enhance flavor.

- Entourage Effect: The theory that cannabinoids and terpenes work synergistically, producing effects that differ from isolated compounds alone.

- Terpenes: Aromatic compounds found in cannabis (and many other plants) that influence scent, flavor, and potentially the overall experience. Examples include myrcene, limonene, and pinene.

- Cannabinoids: Active chemical compounds produced by cannabis that interact with the body’s endocannabinoid system. THC and CBD are the most well-known, but more than 100 have been identified.

- Endocannabinoid System (ECS): A biological system in the human body involved in regulating mood, pain, appetite, sleep, and immune function. It includes CB1 and CB2 receptors that interact with cannabinoids.

- Microdosing: Consuming very small amounts of cannabis to achieve subtle therapeutic or mood effects without significant intoxication.

- Bioavailability: The proportion of a substance that enters the bloodstream and produces an active effect. Different consumption methods (inhalation, ingestion, sublingual) vary in bioavailability.

- THCA / CBDA: The raw, acidic forms of THC and CBD found in fresh cannabis. These compounds convert into their active forms through decarboxylation (heat or aging).

- Cannabis Strains: A cannabis strain refers to a specific Indica, Sativa, or Hybrid variety or cultivar of the cannabis plant, selectively bred to express unique combinations of cannabinoids, terpenes, flavors, and growth characteristics.

- Chemovar (Chemotype): A more scientifically accurate term than “strain,” referring to a cannabis variety defined by its unique chemical profile rather than just its name or lineage.

The Future Is Green

Cannabis has returned from the fringes to the center of global discourse. Whether used as a sustainable alternative to plastic (hemp), a treatment for chronic illness, or a tool for relaxation, the plant’s versatility is unmatched. As we look toward 2030, the focus shifts to sustainability, social equity for those harmed by prohibition, and the continued unlocking of the plant’s genetic secrets.

The story of cannabis is no longer a story of crime; it is a story of science, health, and a thousands-year-old relationship with mankind that is just getting a second wind.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

When was cannabis first used by humans?

Archaeological evidence suggests usage as early as 8000–10,000 BCE in regions like the Oki Islands and mainland China. It was originally valued for its fibers (“retting”) and later listed as one of the “Five Grains” in ancient China.

How did cannabis enter Western medicine?

Cannabis became part of Western pharmacopeias in the 19th century, often used for pain, migraines, muscle spasms, and insomnia. Irish physician Dr. William Brooke O’Shaughnessy documented its therapeutic potential after observing its use in India.

Did historical figures use cannabis medicinally?

According to historical accounts, Queen Victoria may have used cannabis tincture for menstrual pain relief under the care of her physician, Sir J. Russell Reynolds, who praised its medical value.

What is the Endocannabinoid System (ECS)?

Discovered in the 1990s, the ECS is a biological signaling network in the human body. It acts as a “master regulator” for sleep, mood, pain, and immunity. It contains receptors (CB1 and CB2) that interact with the plant’s cannabinoids.

What is the difference between THC and CBD?

THC binds primarily to CB1 receptors in the brain and produces psychoactive effects (the “high”), while CBD interacts differently, often targeting peripheral systems to reduce inflammation, anxiety, and pain without intoxication.

Is cannabis legal in Europe?

Regulations vary by country. While not fully legalized EU-wide, countries like Malta have legalized personal use, Germany now operates “Cannabis Social Clubs” and home grow rights, and nations like Switzerland and the Netherlands are running pilot programs.

What major early cannabis law affected global prohibition?

The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 in the U.S. imposed prohibitive regulations that dismantled legal hemp production and medical cannabis use, setting a precedent for the global wave of cannabis criminalization in the 20th century.

How did cannabis become globally prohibited?

In 1961, the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs codified cannabis prohibition internationally, pressuring signatory nations to criminalize the plant and dramatically limiting research and legal access worldwide.

What is the significance of the 2025 rescheduling?

In 2025, the U.S. government reclassified cannabis to Schedule III, formally acknowledging that it has “currently accepted medical use.” The move signals an end to the most restrictive phase of federal prohibition and opens the door for expanded clinical research and tax reform.

What affects the experience of cannabis edibles?

When ingested, THC is converted in the liver into 11-Hydroxy-THC, a more potent compound that produces delayed but often stronger and longer-lasting effects compared to inhalation.

What are minor cannabinoids, and why do they matter?

Beyond THC and CBD, cannabis produces dozens of cannabinoids such as THCV, CBN, and THCA, each with unique potential effects—e.g., THCV may influence appetite, while CBN is linked with sedative properties. The science is still evolving.

How does the ECS impact human physiology?

The ECS is present throughout the body, including the digestive tract, immune system, and brain. It helps regulate appetite, inflammation, mood, coordination, and memory by interacting with cannabinoids such as THC and CBD.

What are the main ways people consume cannabis today?

Cannabis can be smoked, vaporized, ingested as edibles, taken as tinctures or oils, or applied as topicals. Each method influences onset time, bioavailability, and the intensity of effects.

What common medical conditions is cannabis used for?

Cannabis is widely used to help with chronic pain, nausea (especially in chemotherapy), appetite loss, anxiety, insomnia, and certain neurological conditions, often as part of a broader treatment strategy.

Is cannabis harmless?

No. While cannabis can provide therapeutic benefits, it is not entirely harmless. Heavy or frequent use may impact physical and mental health, and effects can vary depending on dose, strain, and individual biology.

More from Soft Secrets: