PK

About: Phosphorus is indispensable for photosynthesis. It is the energy source for plants transferring energy generated in PS and during respiration, from the release of stored energy in carbohydrates. Phosphorus—one of the components of DNA, many being enzymes and proteins—is associated with overall vigor, resin, and seed production. Phosphorus is extremely important to the health of young plants.

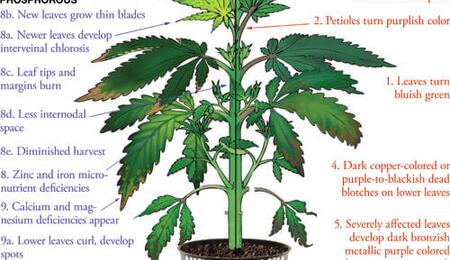

Phosphorus (P)—mobile (essential)

Cause: When a phosphorus deficiency does occur, the pH has usually drifted up too high, beyond 7.0, which makes the macronutrient unavailable for uptake because it becomes unavailable as it changes ion form. Cold temperatures [below 50°F (10°C)] impair phosphorus uptake. Deficiencies are aggravated by clay and soggy soils. Other causes include acidic growing medium, an excess of iron and zinc, or soil that has become fixated (chemically bound) with phosphates. However, adequate zinc is necessary for proper utilization of phosphorus.

Confused with: Zinc deficiency, cold temperatures

Solution: Naturally occurring phosphate compounds accessible for uptake by roots are seldom available. Phosphorus is bound in organic compounds and is released via decomposition affected by soil life. Bat guano is a readily available source of phosphorus. Steamed bone meal, barnyard manure, and compost are the next-best sources. Thoroughly mix in the organic nutrients into living soil. Always use finely ground organic components that break down and become available quickly. Prevent deficiencies by mixing a complete organic fertilizer that contains phosphorus into the growing medium before planting. Outdoors, mix fine, steamed bone meal and pulverized rock phosphate into soil the year before planting. Use phosphoric acid to lower the pH to within a range of 5.5 to 6.2 in hydroponic units, and lower the EC too. Correct the pH (6.0–7.0 for clay soils and 5.5–6.5 for potting soils) to facilitate phosphorus availability. If the soil is too acidic and an excess of iron and zinc exists, phosphorous becomes unavailable. Cannabis absorbs inorganic phosphates in ionic form only. Check with your local hydroponic store for appropriate phosphorous-rich, properly formulated nutrient mixtures. Use soluble forms of phosphorus when soil temperatures are below 50°F (10°C).

Excess: Relatively common, especially during flowering. In fact, an excess of phosphorus is promoted to thicken flower buds and add weight to final harvest. Excess is usually caused by adding too much high-phosphorus fertilizer in an available form. Toxic signs of phosphorus may take several weeks to surface, especially if excesses are buffered by a stable pH. Symptoms manifest in the form of micronutrient deficiencies in zinc, which is the most common, and iron. Also, as phosphorus availability increases, calcium and magnesium availability drops. If signs of zinc and iron deficiencies are present, phosphorus could also be lacking. Excess chemical-based phosphorus in cannabis buds during flowering causes a “chemical” taste when smoked.

Cause: Many cannabis varieties can tolerate high levels of phosphorus. Available phosphorus builds to toxic levels if heavily applied and not leached from soil.

Confused with: A deficiency of zinc, iron, magnesium, or calcium

Solution: Raise the pH. Phosphorus does not leach very well so leaching the growing medium has little effect. It just changes form and can combine with calcium to form insoluble compounds.

Potassium (K)—mobile (essential)

About: Potassium helps combine sugars, starches, and carbohydrates, and is essential to their production and movement. Potassium is vital to growth by cell division. It increases the chlorophyll in the foliage and helps to regulate stomata openings so plants make better use of light and air. It is necessary to make proteins that augment oil content and improve flavor in cannabis plants. It also encourages strong root growth and is associated with disease resistance and water intake. The potash form of potassium oxide is (K2O). Soils with a high level of potassium increase a plant’s resistance to bacteria and mold.

Deficiency: Potassium deficiencies are common in indoor gardens, less common in greenhouses, and somewhat common outdoors. Potassium deficiency causes the internal temperature of foliage to climb; beyond 104°F (40°C), it causes protein in cells to burn and degrade. To cool down leaves, evaporate moisture. Evaporation is normally highest on leaf edges, and that’s where the burning takes place. Up to 70 percent of a plant’s energy is “burned” to keep cool. Potassium in excess also moves to these far areas, pores at the ends of the veins, and accumulates, causing this burn that is often confused with general salt burn but is not. The chlorosis must be seen first and a dulling in the cuticle layer of the leaf, all on older leaves. Plants with a minor potassium deficiency appear healthy; leaves are a little too green and have a dull tone. Stems thin and branching may increase. Young leaf fringes and tips discolor turning a rusty brown, dehydrating and curling up. Progressively greater numbers of older leaves (first tips and margins, followed by whole leaves) develop rust-colored blotches, turn dark, and die. Stems often become weak, scrawny, and sometimes brittle. Deficient plants become very susceptible to disease and pest attacks. Flowering is retarded and greatly diminished.

Cause: Potassium is usually present but fixed or bound in humus-rich and clay soils, often locked in by toxic fertilizer (salt) buildup. Excess sodium in the water source that has built up in soil, calcium magnesium and phosphorus and cold weather impair uptake of potassium.

Confused with: Endema (an abnormal accumulation of fluids) or spots caused by bacteria or fungi. Absorption of magnesium, manganese, and sometimes zinc and iron is also slowed. Burned leaf margins are also caused by low humidity and overall fertilizer (salt) burn.

Solution: Leach the toxic salt out of the soil by leaching heavily with clean water. Apply a well-balanced N-P-K fertilizer with high potassium content. Organic gardeners add fast-acting potassium in the form of liquid kelp or potash. Potassium is absorbed quickly and deficiency symptoms should disappear in a few days. Add slow-acting granite dust and greensand to outdoor planting holes.

Excess: Occasionally, too much potassium is a problem, but it is difficult to diagnose because it is mixed with the deficiency symptoms of other nutrients. Excess potassium acidifies the root zone, slows the absorption of calcium, magnesium, and sometimes zinc and iron. Look for signs of toxic potassium buildup when symptoms of calcium, magnesium, zinc, and iron deficiencies appear.

Cause: Potassium has built up in soil, and too much is now available to roots.

Confused with: Calcium, magnesium, and sometimes zinc and iron deficiencies or general salt burn. However, coco coir gives off large amounts of potassium, which is readily absorbed and locks out calcium and magnesium; the result is calcium and magnesium deficiency symptoms but with tip and later marginal leaf burn from potassium accumulating at these points. True salt burn comes not from too many ions in the tissue but from a reversal of the osmotic gradient, pulling water out of the plants not moving it into the plant. The fix in coco is to increase the EC, not back it up and leach.

Solution: Leach the growing medium of affected plants with a very mild and complete fertilizer solution. Severe problems require that more water be leached through the growing medium. Leach with a minimum of three times the volume of water for the volume of the growing medium.