The State of Oregon is Pioneering Liberal Drug Laws

Oregonians have a rare privilege when it comes to recreational drugs. Possession of small amounts of methamphetamine, LSD, oxycodone, cocaine, heroin, and other substances is no longer punishable in Oregon. With its new approach, the state now has similar laws such as Portugal, the Netherlands and Switzerland, countries that have already decriminalized small possessions of hard drugs.

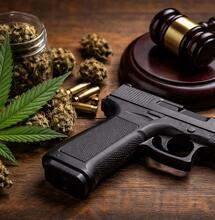

Some called it "the big experiment," and others "a revolutionary move," decriminalizing hard drugs took hold in Oregon on February 1 this year. The new legal measure followed after an overwhelming vote on Prop 110 in the 2020 elections and made personal possession of drugs a subject of civil citation and a $100 fine. An Oregonian caught with up to 2 grams of methamphetamine or cocaine, 40 hits of LSD or oxycodone, or up to a gram of heroin will avoid facing the prospects of jail time. Advocates pushing for systemic change in the US drug policy dubbed the measure a major victory.

Oregon has reeled extraordinarily high rates of drug and alcohol addiction while lacking recovery services infrastructure and resources. Supporters of the measure said criminalizing drug possession was not working. One of the goals of the new radical bill was prioritizing treatment in cases where a person is seen abusing a substance instead of imprisonment and charging a criminal record that will haunt the person for a lifetime.

Marijuana tax money funds Oregon's "big experiment" drug laws, especially the state's addiction recovery centers imagined with the new regulations. The "Treatment and Recovery Services fund" active under Measure 110 is also anticipated to allot cash on housing and job assistance and thus provide long-term support for people struggling with severe drug addiction.

The law esteems the opening of fifteen 24/7/365 Addiction Recovery Centers throughout the state of Oregon by October 1, with one center functioning within each existing coordinated care organization service area.

Marijuana tax revenues peaked at $133 million in Oregon in 2020, a 30% increase over the previous year and a 545% increase from 2016 when the state began collecting tax from legal, registered canna-businesses and dispensaries. Schools, state police, mental health services, cities and counties also receive a chunk of the state's pot taxes.

Oregon was one of the first states that decriminalized marijuana possession back in the 1970s. The state officially legalized marijuana in 2014. Lawmakers in the state have no plans whatsoever to legalize and regulate a market of hard drugs.

Decriminalizing drugs is expected to lower the number of Oregonians who are convicted of a felony or misdemeanor possession of controlled substances. About 3,700 people annually are estimated to avoid persecution with the new regulation in place. The measure also targets reducing the racial and ethnic disparities in convictions and arrests.

When Portugal introduced a similar drug use law in 2000, it took the European country several years of transition however. The country's effort to replace judges, jails and lawyers with addiction specialists, doctors and social workers paid off. Overdose deaths dropped while the number of people treated for drug addiction in the country rose 20% between 2001 and 2008. What Portugal did, it treated addiction as a public health crisis. Anyone caught with less than a 10-day stash of drugs is directed for a mandatory medical assessment.

If the Oregon initiative is to yield success by 2030, the state may need additional federal funding. Besides the money poured in from cannabis revenue. Federal money would expand treatment under Measure 110. But because the State of Oregon uses tax revenue from the legal sale of marijuana, which the federal government still classifies as a Schedule 1 substance, the state can't qualify for federal money at the moment.

Insufficient data to determine what treatment protocols work best, lack of instruments to survey treatment efficacy, and shortage of qualified personnel to work in the program are mentioned as system weaknesses. According to experts, these are some areas the State of Oregon must attentively consider as it continues to implement its revolutionary model.

While Oregon transitions to an innovative legal system, research into various, now decriminalized, drugs may evolve as well. Legalizing cannabis had helped re-ignite research into psychedelics after all studies in this field were suspended with the "Controlled Substances Act" from 1970. Since hallucinogenics such as LSD and mushrooms are encompassed with Oregon's regulation, interest in psychedelics has renewed yet again. The desire to find new treatment options for those struggling with mental health conditions is what essentially triggers research into this controversial class of drugs.

Decriminalization is a step in the right direction for Oregon, but there is still a long way to go until the results are there, palpable and appreciable.